For ten consecutive years, Japan has increased its meat consumption; consumption increased by 3.4 percent last year over the previous year to produce the highest level of growth in five years. Beef consumption, in particular, is expected to grow nearly 4 percent this year after two straight years of decline. Japan is already one of the world’s leading countries when it comes to beef consumption, both in terms of total tonnage and per capita. Japan has also consistently been one of the top beef buyers in the world, with 851,000 metric tons imported in 2017, making it the third largest import market in the world. Thus, Japan is an essential market for beef, especially for the United States.

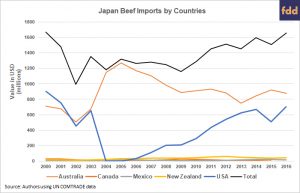

Japan has long been a top consumer of U.S. goods. In 2016, Japan was the fourth largest importing country for both U.S. agriculture and total goods. Total agriculture exports to Japan in 2016 totaled $11 billion (roughly 8.5 percent of overall U.S. ag. exports), of which $1.5 billion was beef. Since 2010, Japan has been the United States’ number one export market for beef. Before 2003, the U.S. and Australia were essentially splitting the Japanese beef market, but in late 2003, Japan banned U.S. beef because of U.S. cases of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE, or “mad cow disease”). Notably in the context of NAFTA, during the ban, Canada and Mexico replaced Japan as the top export destinations for U.S. beef.

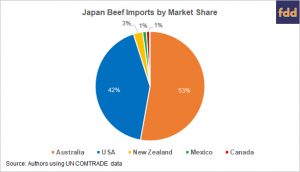

The U.S. cannot rest on its laurels in the Japanese market. The U.S. competes with Australia, New Zealand, and to a lesser extent, Canada and Mexico for the Japanese beef market. After the BSE crisis, Australia replaced the U.S. and is now the largest beef exporter to Japan, with exports totaling $1.8 billion in 2016. The U.S. has been rebuilding since the 2003-2006 ban and currently supplies are just under half of all imports. One factor in Australia’s success has been the Japan-Australia Economic Partnership Agreement (JAEPA) of 2015, which lowers the import tariffs it faces. This disparity is only going to grow with President Trump’s withdrawal of the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).

The World Trade Organization (WTO) states that member countries can’t discriminate against other member countries and can’t offer special favors or rates without making them available to all members–known as most-favored-nation (MFN) treatment. However, the WTO does have exceptions in place that allow members to set up trade agreements or economic partnership agreements that only apply to goods traded within the group. JAEPA, and as stated in a previous article, NAFTA are two examples of this WTO exception. The TPP would be as well, superseding WTO rules and allowing TPP members to receive a better-than MFN rate. The Trump Administration, however, pulled the U.S. out of TPP roughly a year ago.

The lack of an economic partnership agreement between the U.S. and Japan has become evident in the last several months. Japan has enacted emergency tariff safeguards, increasing tariffs on frozen beef to 50 percent from 38.5 percent. This increase is allowed under WTO rules when imports rise more than 17 percent from the previous year in any given quarter. When frozen beef imports increased 17.1 percent from April to June 2017 (Japan’s first fiscal quarter), the emergency safeguard was triggered. The rate increase will be in effect until the end of Japan’s fiscal year (March 31, 2018). By contrast, Australia faces a tariff rate of 27.2 percent.

The TPP would have exempted the U.S. from this “global snapback” tariff as JAEPA has exempted Australia. JAEPA exempts Australia from tariff increases but has also lowered its tariff rate. The standard beef tariff of 38.5 percent the U.S. faces is just 30.5 percent for Australia on frozen beef (phasing down to 19.5 percent over 18 years), and down to 32.5 percent for fresh beef (phasing down to 23.5 percent over 15 years). Not only would the U.S. be saved from tariff increases under the TPP, but the TPP would have set a new fresh and frozen beef tariff of just 27.5 percent in the first year of the agreement, gradually decreasing each year until the final rate of 9 percent in year 16. For evidence that these tariffs matter, look at Japan’s beef imports for August 2017 (first full month of increase). Frozen U.S. beef imports fell 26 percent while Australian imports increased 30 percent. The increased tariff also led to a shift towards chilled beef—which isn’t subject to the increase—seeing U.S. imports rise 55 percent.

JAEPA, with its lower tariffs and exemption from emergency rate increases, gives Australia a substantial competitive advantage in the Japanese beef market. Australia already accounts for over half of all Japanese beef imports, a market share that is all but guaranteed to grow with the United States’ withdrawal from the TPP. Just as a final note, even though the U.S. withdrew from the TPP, the TPP isn’t going away. Negotiations are currently ongoing without the U.S., opening up the U.S. to further market loss if Australia, Canada, and New Zealand are all afforded the lower beef tariffs under the TPP.